A new capital exodus is reshaping the Chinese financial landscape—and it appears to be headed straight for Hong Kong.

In the first half of 2025, companies like Hengrui Pharmaceuticals and CATL raised a combined $5.3 billion through share offerings in the city. EV maker Seres is eyeing another $2 billion. Even Shein, the fast-fashion juggernaut once expected to list in London, is reportedly reconsidering Hong Kong. The shift is unmistakable: with $9.8 billion raised by midyear—more than double the mainland’s $3.9 billion total—Hong Kong is on track to become the world’s leading IPO hub.

But this IPO boom masks a more sobering trend for dividend-focused investors. Behind the headlines and capital inflows lies a deeper problem: China’s corporate fundraising appears to be driven by urgency over strength. And that urgency doesn’t bode well for shareholder payouts.

From Beijing to Victoria Harbour

The surge in Hong Kong IPOs appears to be less a vote of confidence in the city than a sign of frustration with mainland exchanges. In Shanghai and Shenzhen, regulatory bottlenecks, market volatility, and shifting political winds have made it increasingly hard to go public.

Even heavyweights like Hengrui and CATL, already listed on the mainland, encountered roadblocks in their push for secondary listings. For years, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) resisted such moves, worried they would depress valuations at home. But with the Hang Seng China Enterprises Index climbing 50% since January, that resistance appears to be easing significantly.

The broader backdrop is a sharp cooling of China’s IPO pipeline. After hitting a record $81 billion in 2022, mainland listings dried up when equity markets slumped the following year. Only 100 companies went public in 2024—the lowest in over a decade. At the same time, some sectors, such as cosmetics and liquor, have found themselves effectively blacklisted unless they align with the state’s strategic goals. Some suggest that regulators maintain a “floor” on the Shanghai Composite Index, using IPO approvals to manipulate sentiment. As a result, more firms appear to be turning to Hong Kong not necessarily for better valuations or looser rules, but because they do not have another choice.

Raising Capital, Skipping Payouts

That desperation has a cost. Many of the companies now sprinting toward the Hong Kong Stock Exchange aren’t flush with cash. Consider Seres, the Huawei-backed electric vehicle maker operating under the weight of U.S. sanctions. While its IPO may help fuel expansion, investors hoping for dividends will likely be left waiting. CATL, another standout in China’s EV supply chain, tells a similar story—strong on innovation, but short on surplus cash. Both companies operate in capital-intensive sectors where reinvestment takes priority over shareholder payouts. In this climate, income investors should temper expectations. Hong Kong’s IPO pipeline may be full, but few of those new listings will be issuing meaningful dividends anytime soon.

Geopolitics Tighten the Screws

If regulatory obstacles are one side of the dividend equation, geopolitics is the other. Tensions between the United States and China remain a drag on investor confidence. The Biden administration’s restrictions on American investment in sensitive Chinese sectors like AI and semiconductors have made some profitable firms look toxic to global capital. That risk premium can translate into tighter margins and, predictably, lower dividend potential.

There have been flickers of hope, however—tariffs on both sides were slashed in the surprise 90-day truce on 12 May. Wall Street has rallied, with the Nasdaq jumping 7.2% in the weeks following the deal. But for Chinese companies, the truce is too short to reframe capital plans. The default mode remains: conserve cash.

At home, the economic picture does not appear to be helping. Consumer demand and the property market remain sluggish. A recent independent macroeconomic research report by Chinese firm Capital Economics noted a downturn in the composite Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), pointing to slowing GDP growth. When profits come under pressure, dividends are often the first to go.

A New Corporate Mindset

Just as important as a strong balance sheet is mindset. A cultural shift is underway in how Chinese firms—especially those going public in Hong Kong—view capital.

Listing on the mainland once came with unwritten expectations: stability, accountability, and steady payouts. But as firms pivot to Hong Kong and global markets, the calculus is changing. Flexibility and access to capital now outweigh dividend regularity, especially in the tech sectors. This trend appears to be even stronger among firms tied to national strategic goals. Whether it’s chipmaking or clean energy, the focus is on scale, not shareholder yield. In many cases, the state itself appears to be more focused on long-term technological self-sufficiency than in rewarding investors.

Even among less “strategic” sectors—consumer goods, lifestyle brands—the dividend picture remains cloudy. These firms often face bureaucratic delays even in Hong Kong, and when they finally do list, most proceeds are used to plug funding gaps or meet new compliance hurdles. Little is left for shareholders.

Yield Outlook

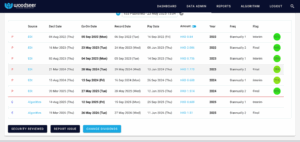

For now, the best dividend stories out of China are those that already exist. In March, CK Hutchison—long considered a reliable dividend payer in Hong Kong—cut its final FY24 dividend by nearly 15%, lowering it to HK$1.514 from HK$1.775 the year before. The company cited “volatile and unpredictable” market conditions following a decline in underlying profit. Dividend forecasting platforms like Woodseer have since adjusted expectations more broadly in response.

The bottom line: investors chasing stable income will likely have to look outside the Greater China region or limit themselves to a handful of established names with robust cash flow and low leverage. The IPO wave, impressive as it may seem, does not appear to be built on a foundation of payout potential.

A Listing Frenzy

Hong Kong’s resurgence as an IPO destination is an important financial story. It speaks to the city’s enduring role as a bridge between China and global capital. But for investors focused on income, the headline numbers can be misleading.

This is not a market flush with profits to share. It’s one in which companies are raising money to stay solvent, fund strategic bets, or sidestep regulatory hurdles. The dividend, once seen as a marker of corporate health and investor respect, has been relegated to an afterthought. Until China stabilizes its policies, calms its politics, and rebuilds domestic economic momentum, dividend seekers may find slim pickings in its freshly listed stocks. For now, the message appears to be that in China’s capital markets, the cash is coming in—but not going out.

Written and Researched by Patrick Haynes – Patrick is a Finance and German student at Washington and Lee University with a focus in equity markets and behavioral finance. Passionate about financial literacy and market trends, he aims to bridge the gap between academic theory and real-world application. Connect with him on LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/patrick-haynes-08628131b

There is an inherent risk involved with financial decisions. The information in this article is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide financial advice. Views expressed are those of the author and are not necessarily those of the company.