With more than 200 countries and an estimated 10,000 athletes in action to competing, Paris is in full swing hosting the ancient old competition of the Olympics. Historically, the preparation for the Summer Olympic Games has brought both positive and negative economic outcomes for host cities, impacting not only the local economies but the entirety of the host state, as well as associated companies and partners.

Infrastructure development: Benefits and Challenges

Notably, Commitment to developing the infrastructure is a critical aspect of hosting the Summer Olympic Games as it can bring substantial economic gains but can also cause significant strains, some foreseen and some unforeseen. Taking a look at the past three Summer Olympic Games in London (2012), Rio de Janeiro (2016), and Tokyo (2020), it is possible to dissect how the modern Olympics games have influenced the internal infrastructure of and how this may influence Paris, both currently and by legacy, as it navigates the role of being the 2024 host.

The significance of legacy- the revitalizing of East London

The 2012 London Olympic Games, seen widely as an infrastructural success, stimulated the regeneration of East London through the “Strategic Regeneration Framework”; the East of London had an area that had been perceived to have been neglected for a significant amount of time, but the Olympics rejuvenated the area significantly, with a state-of the art shopping center opening in 2011, in Stratford, a stones throw away from the Olympic Park, as well as various infrastructure projects, and active reaching out to the local community. The five host boroughs – Greenwich, Hackney, Newham, Tower Hamlets, and Waltham Forest – benefitted from the East Village housing development, now contributing to local commerce with shops and restaurants. The goal of the “Strategic Regeneration Framework” was to develop these poorer neighborhoods to the scale needed to host the games and continue to prosper in the years following the event.

The Transformation of Public Transportation- Rio 2016

Hosting the 2016 Summer Olympic Games saw significant improvements in Rio de Janeiro’s public transportation system. Enhancements in the Bus Rapid Transit, the Metro, and the Light Vehicle Rail System enabled the city to manage the daily travel of 2.3 to 3 million people. These developments were crucial in order to support the influx of visitors and athletes during the Games as well as provided lasting benefits to the city’s residents.

Building for the future- Tokyo 2020

For Tokyo the 2020 Summer Olympic Games saw the creation of eight permanent venues, including the National Stadium, Tokyo Aquatics Centre, and Ariake Arena, among others. These investment were made in the hope that they would continue to prosper following the Games. The new infrastructure was designed to host both domestic and international athletic events, ensuring that Tokyo would generate revenue post-Olympics on a smaller, more frequent scale, leading to increased business and tourism from athletes and spectators.

How does the investment in infrastructure development act as a catalyst for other economic benefits?

Investing in infrastructure intends to create a chain reaction of positive economic stimuli. London’s Queen Elizabeth’s Olympic Park, built to host the 2012 events, has since attracted more than 16 million visitors. Tourists, drawn by the former global stage, flock to East London, stimulating local businesses and cafes surrounding the park. The London Legacy Development Corporation predicts that by 2025, 40,000 jobs will be created thanks to the legacy of the Olympic Park. Additionally, the primary Olympic Stadium’s purchase by West Ham United has contributed to its continued use.

The improved transportation in Rio has led to a 4.8% increase in tourism post-Games, generating 6.2% more revenue for the sector compared to the year prior to hosting the Olympics. Enhanced public transportation also improved job accessibility by making commutes easier.

Tokyo’s investment in permanent facilities continues to yield benefits beyond the Olympics, supporting athletic development and sports competition. The new infrastructures were built with the future in mind, designed to host both domestic and international athletic events, allowing Tokyo to generate revenue post-Olympics on a smaller, more frequent scale, leading to increased business and tourism from athletes and spectators.

What are the economic concerns of hosting the Summer Olympics?

Despite the potential benefits, hosting the Olympics also poses significant economic risks. The deep expenses associated with investing in infrastructure and the money invested for hosting the Olympics can result in unfavorable outcomes, the privilege of hosting the world’s most revered sporting event puts a nation in the global spotlight- but are the returns worth the significant amount of outlay for this opportunity.

While an increase in employment may seem like a benefit, it is often temporary. For instance, East London’s unemployment fell to 42,000 leading up to the 2012 games but such benefits may be short-lived, with unemployment rates potentially returning to pre-Olympics levels after the event.It is arguable that the facade of the Olympics’ ability to create jobs from the construction of infrastructures, managing an influx of spectators, and other Olympic-related work has been overstated. These benefits are temporary arguably, and unemployment rates may return to pre-Olympic levels after the summer. These levels may resume to pre-olympic levels.

“White elephant” facilities are also a concern. These are infrastructures that were built for the Olympics but are no longer used or serve as revenue generators. The Olympic Park built for the 2016 Summer Games in Rio is more deserted than a lively attraction. Additionally, more than 90 percent of the condominiums built across from the Olympic Park in the form of 31 towers are vacant. These sites have failed to generate long-term profit.

Unpredictable factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic during the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, can also disrupt economic gains. The absence of spectators resulted in an $800 million loss in ticket revenue, worsening the financial strain from nearly doubled hosting costs.

The pitfalls of dedicating large sums of money to financing the Olympics come with risks. It raises the question of how a city can capitalize on hosting the Olympics in a way that outweighs the opportunity cost of allocating its resources and budget in other ways.

How is the International Olympic Committee working to address the financial burden of the Olympics?

To combat the criticism that the Olympics lead hosts into long-term debt due to selection process dues and the expenses required to prepare for the mass of tourists and the infrastructure needs for the sporting events, the International Olympic Committee has revised its bidding process. Thomas Bach, the IOC President, approved his Olympic Agenda 2020 in 2014, which emphasized flexibility, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness. [JO10] The bidding process was reduced to two stages: a continuous dialogue and a targeted dialogue. The continuous dialogue involves a conversation between aspiring hosts and the Future Host Commission as prospective nations develop their unique vision for the Games. The parties chosen to enter the targeted dialogue become “preferred hosts” and engage in conversation with the IOC and FHC.

Hosts must use existing venues unless new construction adds long-term value, inspired by Los Angeles’ profitable use of pre-existing venues during the 1984 Summer Olympics. This move was worth $15 million in profits. The International Olympic Committee states that bid budgets have decreased by 80 percent since the initiative to maximize pre-existing arenas. The goal is to optimize the benefits of hosting the Olympics by creating an enduring legacy that sparks economic growth.

Looking into the future of Paris post hosting…

For the 2024 Summer Olympics, Paris has identified Seine-Saint-Denis, a northeast neighborhood, for regeneration. The goal is to foster economic development similar to London’s East Village. From the addition of cycling lanes to parks, the hope is the Games will spark growth in the area. The Aquatics Center is a permanent facility designed for residents to use for sporting practices after the summer, fostering an active community in Seine-Saint-Deni. The goal is for this economically disadvantaged neighbourhood to transform into a thriving residential district with the exposure and rehabilitation brought by the Olympic Games. Only time will tell if this plan succeeds or if Paris will contribute to the list of “white elephant” infrastructures created by the Games.

Paris aims to enhance its transportation system by extending select subway lines and a commuter train, spreading costs due to the long-term benefits of increased travel capacity. In alignment with the Olympic Agenda 2020, 95% of events will be held in pre-existing venues, maintaining the cost at 11.8 billion euros, lower than past games.

The Olympic Agenda 2020, approved by IOC president Thomas Bach, emphasized flexibility, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness.

Since the initiative to maximise pre-existing arenas, bid budgets have decreased by 80%. This strategy aims to optimize the benefits of hosting the Olympics by creating an enduring legacy that sparks economic growth.

How does this issue relate to dividends?

Hosting the Olympics can accelerate urbanization, potentially acting as dividend payments in the years following the event. However, the economic boost may be short-term, with the potential for financial difficulties afterward. A few examples using Woodseer data is used to describe this pattern.

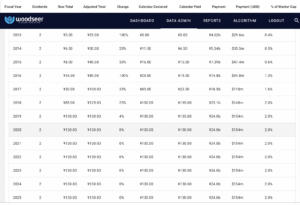

In 2015, Taisei Corporation secured the contract to build the National Olympic Stadium in Tokyo for the 2020 Summer Games. Woodseer Dividend Forecasting data shows a 100% increase in dividend payments from the year of the deal to the next, likely due to substantial revenue from the project. However, as the stadium neared completion in 2019, dividend growth slowed, and post-Olympics, there was no increase in dividend distributions.

This example reflects the common economic pattern of a short-term boost followed by a plateau or decline after the Olympics. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic also likely played a role, so attributing the downturn solely to the Olympic project’s completion would be an oversimplification.

Adidas provides another illustration of the Olympic effect on dividends. As the official sportswear partner of the London 2012 Summer Olympics and a sponsor of numerous teams and athletes in the Rio 2016 Summer Olympics, Adidas saw significant increases in dividend payments during these Olympic years, according to Woodseer Dividend Forecasting data. The increase in 2012 was 35% and a 25% increase was seen in 2016. This rise can likely be attributed to enhanced brand exposure and revenue from Olympics-themed product lines.

Prosegur, a security firm tasked with protecting Spanish athletes during the Rio 2016 Summer Olympics, experienced a dramatic 96% increase in dividend payments that year, according to Woodseer data. The upward trend continued into 2017 with an increase of 170%, reflecting the financial benefits from their Olympic involvement. But in 2018 the experienced a decrease in dividend payments of 79%.

Can Paris Turn Olympic Glory into Enduring Success?

Local businesses in Paris have and will see increased profits from tourism and city advertisements during the Olympics. However, this could be offset by locals avoiding crowds and the excitement waning post-summer.

The challenge for Paris, as with any host city, is to capitalize on the Olympics in a way that outweighs the opportunity cost of allocating resources and budget to other areas. The hope is that strategic planning and sustainable development will ensure long-term benefits, avoiding the pitfalls of past hosts.

The 2024 Summer Olympics present Paris with a unique opportunity to leverage the global stage, enhance its infrastructure, and boost its economy. The ultimate success will depend on balancing the immediate demands of hosting the event with the long-term needs of its residents and businesses.

Written and researched by Annie Jennings